As I mentioned in

an earlier post, I am taking a course at the University of Toronto this term from my mentor's former advisor, who is currently an emeritus professor. This week, the student I carpool with was out of town, so I decided to take the bus in and hang out in town for the afternoon—something I typically don't get to do.

After lunch with a classmate who lives in town, I headed to the

Royal Ontario Museum (ROM): it is a natural history (dinosaurs, ecosystems, taxidermy stuffed animals) and cultural history (First Nations/Native Americans, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, ancient Roman and Greek).

The museum currently has a slightly abbreviated collection due to the renovation work. It was a good way to pass the afternoon: the parts of the collection I saw were pretty good, although endless rows of Chinese ceramics or Roman amphorae are not really my thing. Also, I've probably been spoiled by growing up with the

Museum of Natural History and

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. But the reptile exhibit was good, and their collection of birds was neat. They showed some of their "back collection" (i.e., typically not exhibited)—it is a bit disturbing to see how well dead stuffed birds fit into clear storage tubes—it's like avian Tupperware!

Their Ancient Greece and Rome collection felt, well, a little bit ancient—it seems like it had not been updated since the 1970's, and although the material really doesn't require an extreme makeover or anything, it ended up looking a little bit ratty and neglected. However, one piece of new and interesting information: the etymology of

ostracize: "Greek

ostrakizein: to banish by voting with potsherds." Basically, the Greek legislature would periodically gather and cast votes (written on potsherds) on the man deemed most dangerous to the state, resulting in a 10-year banishment. It was meant as a control on unbridled power. Man… sounds like a good system to bring back.

The ROM is a gorgeous old building (1930's mostly, with a 1980's addition); look at this

picture of the rotunda entrance. Like the

Art Gallery of Ontario, which I visited two weeks ago, this museum is in the process of a major addition by a Big Name Architect (

Frank Gehry for the AGO, and

Daniel Libeskind for the ROM). The new addition is a glass and aluminum clad structure: it is supposed to give the appearance of a geological crystal, growing out of one side of the museum.

They have a

live webcam that lets you track the progress of the project.

I started to write about modern architecture here, but it quickly ballooned into a major essay. I have put it below the cut line; you are all welcome to either read or ignore it.

Anyway, I wrapped up the evening with dinner at a passable Thai restaurant: my original intent was to find a jazz club called Rhodes Restaurant. However, after hoofing it up to that part of town, I found that it had closed down and been replaced: a good reminder that old links often live forever. However, I did get to wander through parts of Toronto that I haven't been to yet (

Yorkville and

Summerhill)

While taking the subway back downtown to the bus terminal, I realized that mass transit is a mode of transportation that I really feel at home and comfortable with, whether it's in Boston, New York City, the Bay Area, Chicago or Montreal. I'd much rather take the bus in from Kitchener to Toronto, rather than drive and worry about parking, even if it takes more time and costs more—I can relax with an iPod and a book, and not think about traffic. I hope that I can always keep my life set up to avoid driving as much as possible.

---------->8---------->8---------->8---------->8---------->8---------->8--------------

These two museum additions make me want to share some thoughts about modern architecture, both as an observer and end user of buildings, as well as a professional in the construction industry. In preparing this piece, I worried it would end up being a rant against modern architecture, but that is not my intent. I don't have any intrinsic opposition to 'new' architecture and innovation; I think I tried to narrow my objections down to some of the worst excesses.

This stems from a discussion with my classmate, who is an architect by training and a building scientist by association. He pointed out that the Gehry addition is priced at $800 per square foot. In comparison, a durable university building is on the order of $300/sf, and normal residential construction around $100-150/sf. When serious money is spent on the Big Name Architect buildings, less remains for, say, running the building (or museum collection), or in the case of university buildings, having the resources to effectively fit out laboratory and research spaces.

Granted, having an world-class architectural landmark is definitely worth a hell of a lot, both in terms of prestige and drawing visitors. Also, I am not in favor of soulless generic buildings—I work on a campus that is filled with them, and my undergrad career was spent on another campus filled with them.

One problem is the commodification of the Big Name Architect: it's an institution's answer to "Keeping up with the Joneses": to have a signature piece as a status symbol. "Oh, you have a Liebeskind? That's nice, but

we have a Gehry." (Heh… all in favor of renaming it the "Status Center…").

A second problem I have with Gehry, in particular, is that his graceful curved building forms, more than anything, seem to demonstrate to me, "we have the power and technology to make buildings like this." I'm reminded of the twelve-year-old architect wannabe that most of us have inside us: "And I'll make it all big and swoopy and curvy and cool," which is then shot down with, "Yeah, how are you going to build it?" Since we now have the technology (CAD software used for designing aircraft) and resources (people willing to spend for a Big Name Architect), we can make these buildings. But to some degree, they feel almost a bit self-indulgent. It gives me greater admiration for the restraint shown by great buildings that use conventional architectural forms, and the fact that artistry shines through despite (or partly, due to) working within those boundaries.

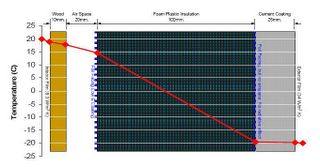

Another problem I have is that, over and over again, these name-recognized buildings sacrifice usability and positive occupant experience in favor of appearance. It goes against my philosophy of substance over flash and appearance. This problem is typical for what is called "magazine architecture"—other critics will laugh when you talk about adding a usability survey when evaluating the architectural value of a building. Services don't work, spaces overheat or are too cold, rain leaks in, etc. This has often been the case with cutting-edge architecture: just read accounts of how badly broken Frank Lloyd Wright's buildings were (Fallingwater, his Usonian houses). As an owner resignedly sighed, while looking at her leaking Wright house, "Well, that's what happens when you leave a work of art out in the rain." Also, often in these buildings, energy efficiency is abysmal and environmental impact is barely considered: things that could be done with incredible success with budgets of these levels.

As an engineer, I could be accused of being overly practical, at the cost of aesthetics, art, and innovation. I'm not trying to denigrate artists/architects because they do misguided things, make my professional life more difficult, or because they're "strange"—exploration is a good thing. I just have specific problems with what is typically sacrificed in the process of these signature buildings. Architecturally significant buildings that are made to address usability, energy efficiency, durability, and environmental impacts are a wonderful thing that the world should have more of.