Thermal Mass is Whomping on my Ass

Apologies for a building-geek post, but I'm currently sweltering in my 89° F (32° C) apartment, and wanted to write something to keep my mind off it, by explaining the science of why I'm sweating in shorts and flip flops. Oh, and the power has gone out too, so no fan. And no dinner. And worst of all, no network. Oh, life is teh sux0r right now.

By explaining my lack of thermal comfort, I don't know if it really helps me to know what happening while not being able to do much about it. I guess it's the feeling that a crash test researcher would have while getting T-boned: Well, looks like I'm about to get hit by a mid-size SUV, which puts the bumper at approximately head level. This will likely result in vehicle intrusion into the passenger compartment: given the lack of airbags on this vehicle, I would estimate a 90%+ chance of serious skull fracture or brain injury. Shit.

Thermal mass is often considered a good thing in energy efficient passive solar design--for instance, see this web page from the California Energy Commission. In short, you can store solar energy collected during the day (either in your floors and walls, or an engineered solution like collection rocks, concrete, or water), and release it at night.

During the summer, thermal mass keeps the hottest part of the day from getting into the building. But remember what I wrote above about releasing heat at night? Yeah--my apartment is the second floor of an uninsulated brick building, so when it gets down to a reasonable temperature at night, the building is still dumping heat from the peak of the day. For instance, it's now midnight, and 77° F (25° C) outside, and 85° F (29° C) inside. And I've been running a pair of fans to flush out my place since about 9 PM, but there's a lot of energy stored in that brickwork. Night flushing used to work fine in my old apartment in Cambridge: wood frame construction with insulation; not as much thermal mass in the interior plaster, plus the insulation isolates the mass from the day's heat.

For the technically minded, thermal mass provides damping of the incoming signal, as well as a phase shift (maybe ~16 hours in my house).

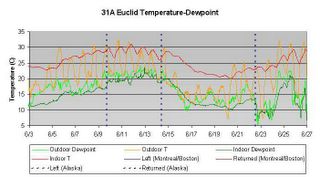

You can see the behavior in the graph below ("next slide please.") The red plot is my apartment's temperature, and the orange is the outside temperature. I caught both times when I was away (and the windows were all sealed up: 6/3-6/9, and 6/14-6/22), as well as when I was around and flushing out the place at night. You can tell when I was around: the red (interior temperature) gets more 'spiky' from the fan use. As you can see, night flushing drops the temperature by 2-4° C at night, but it's still nowhere near how cool it is outside. Also, in the colder period of 6/15-6/22, you can see how well the house holds on to heat.

Apologies for the use of a JPEG for line art; it seems like this photo uploading software doesn't support PNGs or GIFs.

Fuck it. I'm putting up my tent outside.

3 Comments:

Apology accepted.

Hey - why don't you build an air conditioner out of your fan like this civil engineering student at U Waterloo recently did: link.

You can go hang out with him too - I'm jealous!

This post is totally cool.

[Unrelatedly, it was amusing to come home from our long trip away and find that the house was 26C inside at 3 PM, despite it being 32C outside. Foolish me opened all the windows (too stuffy outside, and way too hot upstairs), and it soon equalized...]

Hmmm...maybe we should have you to dinner and pick your brain about building geek stuff. Do you make housecalls?

Post a Comment

<< Home